Graphical User Evolution

Everything started as a problem in XEROX Parc labs in the 70s. A bunch of scientists were experimenting with new ways to make interaction with computers a lot easier than it was back then. It was a time when those rare-to-come-by, bulky, difficult to understand and use machines operated by typing cryptic commands on a clicky keyboard while staring on a black monitor with a blinking dot.

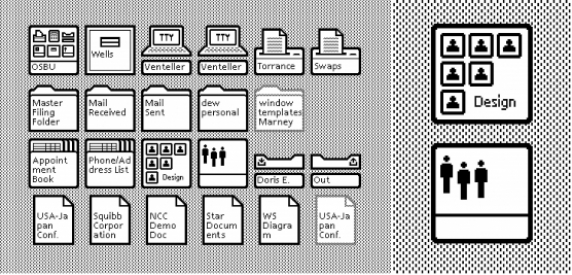

So they came up with the concept of the Graphical User Interface or GUI. In simple terms, a GUI consists of a pointer, a pointing device, icons, a desktop, some windows and menus. Sounds familiar? I bet it does. It was a brilliant design concept that changed forever the way we interact with computers. But why is that?

Without getting into much detail, it's basically because GUIs use metaphors from the physical 3D world we live in. Every command became a series of clicks and drags with the mouse, on little images called icons that represented objects we are already familiar with. If you wanted to erase a file from your hard disk, instead of typing the command 'delete', all you had to do is click on an icon that represents that file and then drag it on another icon that resembles a trash can. It suddenly got so much simpler.

Here's a video of Bill Atkinson at Apple, demoing one of the first GUIs that were later adopted and refined by Apple.

Because we can ...not because we have to.

Good Design Makes A Product Understandable: It clarifies the product's structure. Better still, it can make the product clearly express its function by making use of the user’s intuition. At best, it is self-explanatory.

Dieter Rams, "Ten Principles of Good Design"

So for the past four decades, designers had to use all sorts of realism as metaphors for the physical world, such as artificial light to create shadows and 3D buttons that looked 'clickable', textures, animation and sound effects in order to familiarise the user with the GUI. In many cases the entire interface would look and behave like a real life object or device like a bookcase for an application that stores and displays e-books, a tape cassette recorder for an app that plays podcasts or a calculator that has the same layout as the ones we use in the physical world. These are types of devices that we have come to know as "skeumorphic".

It's also worth noting that although most skeumorphic interfaces tend to look realistic, skeumorphism and realism don't always go hand in hand. There are plenty examples of "flat" interfaces that make use of skeumorphic design. One of the most characteristic ones are the calculator apps we use on our smartphones. As you can see in the image below, the latest version of the calulator on iOS 7 doesn't use any realistic elements but retains the layout of the buttons found on stand-alone calculators.

Fast forward to the present, when computing devices and interfaces have become so ubiquitus that for the first time in interactive design history we don't have to use realism and skeumorphism to "educate" the user about the basics. We can safely assume that in most cases he or she can easily determine the functionality of the basic elements of an interface such as a button, or a menu without the connections to the physical world.

Although we talk about it for the past couple of years, flat design interfaces have existed long before that, but the difference is that now we can safely assume that it is understandable for the average user. And this is truly liberating because it gives us the opportunity to create even more engaging and intuitive interfaces without making the compromises we did a few decades ago, for the sake of familiarity. After all, good design is all about making the right compromises to solve a set of well defined problems.

Flat design as a set of choices, not as panacea.

So does this mean that "flat design" is the only way to go & using any kind of realistic/skeumorphic elements is wrong? Of course not. Each decision to remove a realistic or skeumorphic element should be based on how well the end result serves the purpose of the speficic design. For instance, for the reasons that we discussed above, skeumorphism and realism tend to result in designs that are easier to understand and operate by novice users. So before going "flat", it should be clear whether the end result might have an impact on usability. In addition, good use of certain realistic and skeumorphic elements has the power to recall the memories of interacting with actual physical objects or devices themeselves. This is a great way to evoke the right emotions to achieve the desired user experience. It has been proved that pleasant experiences improve brain functionality for problem solving, which in turn means that by creating a beautiful and pleasant to use product your users will have better chances of figuring out how it works:

In a clever set of experiments, Alice Isen has shown that if people are given small, unexpected gifts, afterwards they are able to solve problems that require creative thought better than people who were not given gifts. The positive affective system seems to change the cognitive parameters of problem solving to emphasize breadth-first thinking, and the examination of multiple alternatives.

Norman, D. A. (2002). Emotion and design: Attractive things work better. Interactions Magazine, ix (4), 36-42.

Let's take a look at an example. Below is a screenshot from the website of Athenos:

Athenos.com is an awarding winning website, and a pretty good example of how flat design aesthetics and choices can be combined with realistic and skeumorphic elements. All the buttons and navigation elements on the site appear as simple and flat white or green rectangular areas which, by today's standards, are very easy to interpret as clickable.

However the rest of the website is filled with all sorts for textures and shadows in order to evoke certain emotions and memories related to the kitchen and the traditional greek cuisine such as wood, marble, linen and paper all combined with images of objects that appear to be overlaid on top of these surfaces using shadows. The end result is a website that uses flat design and realistic elements on the right places to create a fun and memorable experience.

Flat design as a way to future proof your design

Another, more practical, aspect of "flat design" is the way that this approach has the potential to produce websites and applications that can be experienced in multiple devices without looking terrible or oversimplified. In fact, more and more devices are capable of accessing the web so it's practically impossible to predict what combination of hardware and software might be used to access any given website or application. It is evident that a future-proof design has to be as device agnostic as possible.

Flat design has certain characteristics that happen to be excellent candidates for device agnostic design, such as the tendency to use simplified forms, ample white space, grids, typography and icons (instead of bitmaps). If you add on top of this the use of SVG vector elements (which are widely supported and best of all infinitely scalable), you can rest assured your design will appear clear and crisp on every device that supports all these features for many years to come.

Onwards

Flat design is first and foremost an indication that we have made an important evolutionary step in the way we interact with interfaces, especially in websites and mobile applications. Therefore, flat design should be regarded as a set of choices we have the freedom to make, as part of any design process, while being careful before discarding any of the realistic (skeumorphic) elements that might initially seem outdated and unneccessary. Last but not least, flat design lays the foundations to "future-proof" your next website or application for any type of device.